Introduction | Get Started | Learn | Practice | Apply | Explore Further | Checkpoint

In the Budget Estimation module, we will review:

- What is a Budget Estimation?

- Why you need Budget Estimation

- Main uses of Budget Estimation

- Generally accepted good practices

What is Budget Estimation?

Budget estimation refers to the setting of expected expenditures around an organization’s core function, which is to say the overall functionality of the firm. Budgeting is the setting and allocation of capital resources, which are then used to achieve the set or designated targets of the firm.

The process is described as creating an estimate of costs, revenues, and resources over a specified period, reflecting a reading of future financial conditions and goals. One of the most important administrative tools a business has at its disposal, a budget also serves as (1) a plan of action for achieving quantified objectives, (2) a standard for measuring performance, and (3) a device for coping with foreseeable adverse situations.

Why Do You Need to Estimate a Budget?

A Budget Estimate allows a company to effectively allocate its financial resources in such a way that the most strategically important efforts are appropriately funded. This budgeting needs to be focused and clearly prepared so that it covers all of the financial constraints and expectations. So doing means that the financial targets of the firm, and the firm’s viability, are in the financial plan such that routine and daily occurring expenses will be appropriately allocated. When it comes to making space in the budget a new innovation project, having that sound budget estimation in place means that those proposed expenses will not negatively impact the existing operating expenses of the firm.

Budget estimation needs to be done in a proper and meaningful way. It needs to covers all the financial targets that the company needs to achieve in order to be successful. Financial budgeting is also referred to as an investment appraisal as it shows how the investments the company will put forward will fulfill all financial targets.

This module suggests a framework for budget estimation. Since executives, managers, and finance professionals often use related terms interchangeably, it’s worth a moment to consider a few fundamentals.

- Revenue Estimation performed in the executive branch by the finance director, clerk’s office, budget director, manager, or a team.

- Budget Call issued to prior to the creation of the budget to outline what departments need to submit and to recommend goals.

- Budget Formulation reflecting on the past, set goals for the future and reconcile the difference.

- Budget Adoption final approval by the budget.

- Budget Execution amending the budget as the fiscal year progresses.

Main uses of Budget Planning

Budgets and innovation have long been viewed as incompatible. Budgets encourage cautiousness and risk-averseness, while innovation demands creativity and risk-taking. However, an increasingly globalised economy demands that firms achieve both simultaneously. So, how is this being attempted? How are firms seeking to reconcile the two supposedly incompatible imperatives of budgetary control and creative innovation?

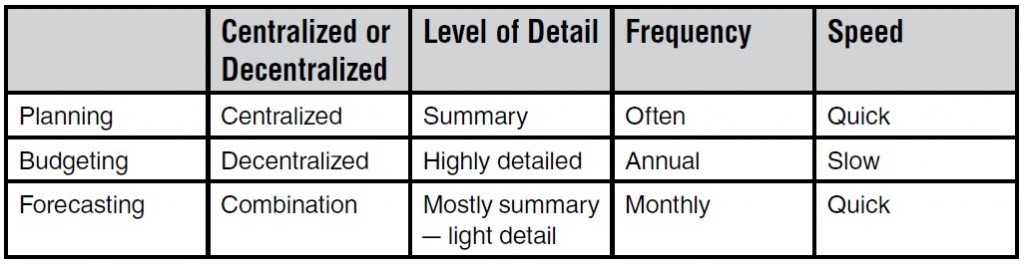

The table below summarizes the key aspects of planning, budgeting, and forecasting.

Given its broad reach and time-consuming nature, budgeting is a part of the business where dramatic improvements can be made. Budgeting is disliked or feared in many organizations because managers see the process as a recurring setup for executive blame and recrimination in the event of negative outcomes they could neither predict nor control. However, when done well, budgeting sets every area of an organization up for success.

Budget holders

Budget holders— the profit and loss (P&L) center managers— dread the onset of a budget cycle, the extra work it is going to entail, and the consequences that will follow if they get things wrong. If previous experience has taught them that the budget is likely to be a platform for shame and abuse, they may treat it as game in which they compete with their peers to make sure it is someone else who becomes the scapegoat. The winner of the game will be the one most adept at hiding sandbags— significant over or underestimations that will help them mask inefficiency and ineffectiveness.

Such manoeuvring aside, budget holders are faced with a substantial problem: how to predict — in detail— variables which they cannot control and may not even understand. Budget holders may be expected, for example, to budget for a range of costs relating to occupancy that are based on centrally negotiated contracts for rent, maintenance, utilities, and so on. There are times that non-financial managers are asked for unfamiliar financial information, rather than the physical cost and income-drivers which they understand so much better. Problems compound if budget holders feel they are working in the dark, without adequate awareness of strategic organizational goals. Not only do they miss the guidance that such information offers, but they can be stressed and negatively motivated by the suspicion that senior management has a hidden agenda.

A sound budgeting process should not focus on the mechanics of data collection but should be seen as promoting transparency and participation in future planning.

Senior management

Senior managers also regard the budget process with a mixture of suspicion and frustration. First, they may be concerned that the budget process bears little relation to their carefully prepared strategic plans. This reinforces any misgivings they have that other budget holders are quietly padding the budget with sandbags (intentionally inflated estimates) and fears that, as in previous years, the budget will contain substantial inaccuracies.

Consequently, senior managers become frustrated by their inability to track underlying assumptions and identify and eliminate the sandbags. An inadequate budgeting system provides little direct access for decision-makers, making it difficult to track progress. It may also prevent condition changes — such as a revised management hierarchy or product portfolio — from being reflected in the budget. A common concern is that the entire budgeting process takes too long.

Management is forced to take valuable time away from operational duties, and the business suffers. Often the budget is not finalized before the start of the financial year, and even then, as soon it’s completed, it’s out-of-date, perhaps because strategic goals have shifted or organizational structure has changed. Perhaps worst of all, executives worry that the predictions they are making to the board and other key stakeholders are not sufficiently substantiated by the targets to which their managers are committed.

Finance department

Just as with senior management, the finance department may be frustrated by time- gobbling budget cycles. Weeks, even months, can be spent struggling with the actual mechanics of the budget process— chasing down submissions, checking for invalid or incomplete data, trying to track and control versions— while responding to queries from multiple stakeholders. Like budget holders, the finance staff work long hours to ensure their tasks are completed on time. The Finance staff workload is some of the most stressful, because theirs is the final step and there are inevitably last minute changes to accommodate as the budget is finalized.

The actual creation of the budget may be complex to create, depending on the size of the organization. In cases where an organization has experienced rapid growth, the system may not have been well structured and significant work may need to go into making what might once have been easy manual process (but now are manual headaches) into automated tasks. Once the budget is in order, Finance staff may have to re-enter the budget data into yet another system to support variance reporting.

Control

The budget is a strategic tool used to delegate authority through the organization and is a fundamental part of operating a business. It assists managers in understanding how they and their departments will be judged by providing quantifiable parameters. It also serves to warn managers of areas that may need particular attention or even corrective action.

The budget process also provides the foundation for periodic forecasts – sometimes adjusted as often as weekly but at a minimum quarterly. In the simplest form, a forecast is a budget revision — at a summary level— that reflects any changes in business conditions. It is a reassessment of key budget assumptions and if conditions or assumptions change significantly, it could prompt a review of the strategic plan. Wile most of the variables in a budget are financial, it is reasonable and expected to include data relating to non-financial goals, which may impact the budgetary income and expenditure detail.

Substantiates information for external use

Although a budgets are generally an internal document, certain external parties—investors or creditors, for example —expect that an effective budgeting system is used to provide detailed support for any business projections. Auditors certainly want to know that the budgeting is robust. Additionally, board members, shareholders, and potential investors like the assurance that the summarized business plans delivered to them reflect a budget sufficiently detailed to support management decision-making. in a publicly traded company, it’s vital that any predictions given to market analysts are based on well- prepared budgets (and forecasts).